In 1932, automotive icon Edsel Ford brought Mexican artist Diego Rivera to Detroit and commissioned the artist to paint frescoes on the walls of the Detroit Institute of Art. Rivera brought his wife, Frida Kahlo, a Mexican folk artist, with him.

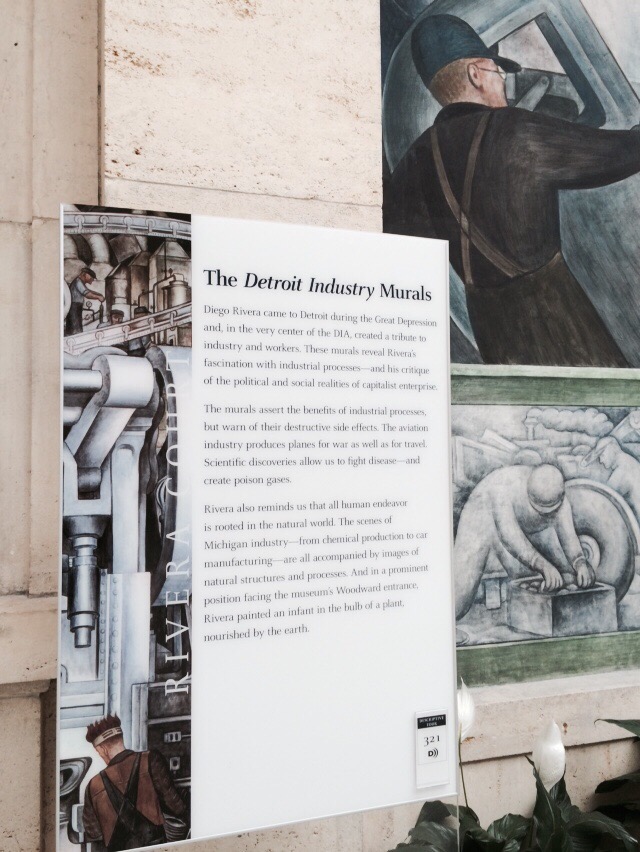

The outcome of Ford’s commission, “Detroit Industry,” was met with mixed opinions when it was unveiled in 1933. Some thought it accurately portrayed gritty factory life in the Motor City during the depression, while others wanted the Communist-tinged murals to be white-washed. Thank God the former prevailed—the Detroit Industry frescoes are indeed the crowning jewel of the Detroit Institute of Arts’ collection, which was recently almost sold off to save the city from bankruptcy.

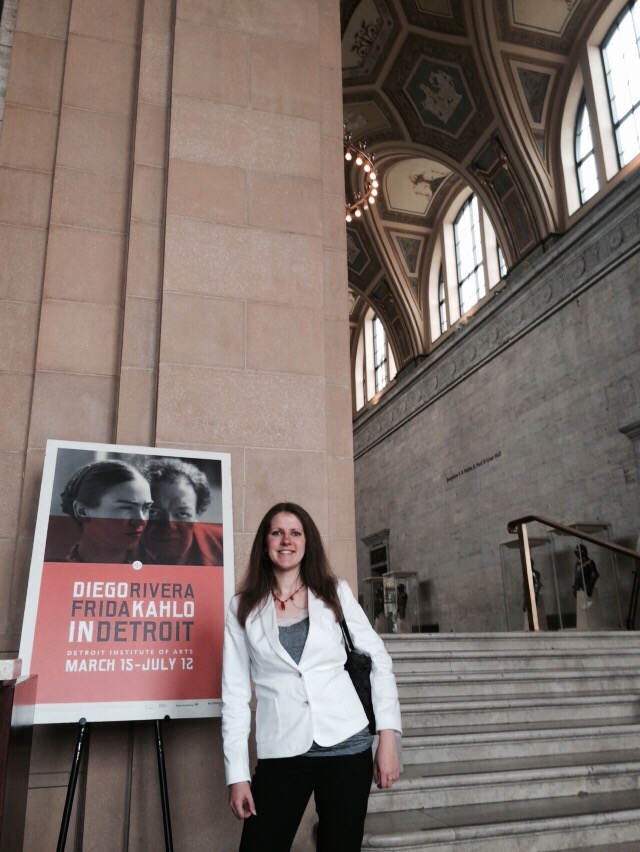

An exhibition 10 years in the making, one can only imagine the volume of art lovers and historians that have been and will be drawn to the show, which runs through July 12th and costs $12 for a self-guided audio tour. Detroit is the only city in the world to boast the honors of the show, just like it is the only museum in the world with the masterpiece “Detroit Industry” literally decorating its walls.

This influx of tourism dollars is welcomed at a time when both the city of Detroit and the DIA seem to be part of a renaissance in which the city is re-inventing itself with a contagious entrepreneurial spirit. Motown went from holding the title of the richest city in America in the 1950’s to being the poorest during the recent bankruptcy. Indeed, the resilience of the great industrial city of Detroit is reflective of the hard work portrayed in Rivera’s murals.

While the exhibition space is rather dark and juxtaposes Rivera’s massive scale work with Kahlo’s smaller, more self-reflective paintings, the murals at the end are in an atrium that is brightly illuminated with natural light. This juxtaposition was not lost and resembles the light at the end of a long negotiation between the DIA and the City of Detroit that culminated in last November’s “Grand Bargain” in which the museum agreed to pay the city $100 million (to help cover pension costs) over 20 years to take ownership of the DIA collection, which had formerly belonged to the city.

“Within the frame this exhibition sets around Rivera’s frescoes, Kahlo’s development is a small vivid sidebar of more than equal weight. Her work is everything Rivera’s art is not: small in size and suffused with personal emotion and existential torment. If Rivera’s frescoes are a kind of cathedral and also a colossal period piece, Kahlo’s small paintings are portable altarpieces for private devotion and a high point of Surrealism that speaks to us still.” New York Times

The couple spent a year in Detroit, culminating in Rivera’s masterpiece and virtually ended his career with the submission of drawings to the Rockefellers in New York City proposing to paint a mural that more boldly displayed Communist propaganda that had been more subtly included in the artist’s Detroit frescoes. This was done so as not to offend his patron, Mr. Ford, who paid Rivera a $20,000 commission fee (the equivalent of a quarter million in today’s dollars) to paint the walls of the DIA. The Rockefellers declined the artist’s submission.

During their time in Detroit, the couple suffered a miscarriage that is graphically portrayed in Kahlo’s painting, “Henry Ford Hospital.” My favorite painting was Kahlo’s self portrait with her pet spider monkey at the end of the show. Kahlo’s work has never before been featured at the DIA, and this show includes 23 of her paintings and drawings that make up the over 70 pieces on display in “Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in Detroit.” It was in Detroit that Kahlo forecast her future fame.

Their time in Detroit may have been short-lived, but the persuasive influence on their work and evolution as artists is clearly evident in the exhibition. After leaving Detroit, the tumultuous couple divorce then later remarried and always remained supportive of each other’s art.